International editor, reporting from the occupied West Bank

Oren Rosenfeld/BBC

Oren Rosenfeld/BBCMeir Simcha agreed to talk, but he wanted to do it somewhere special, because for him, this is a special time. In a place where nation, religion and war are linked inextricably with politics and the possession of land, Simcha chose a patch of shade under a fig tree next to a spring of fresh water.

From his dusty car, a small Toyota fitted with off road tyres, he produced a bottle of juice made from fruit and vegetables.

“Don’t worry, there’s no extra sugar,” he said as he poured it into plastic cups.

Simcha is the leader of a group of Jewish settlers steadily transforming a big stretch of the rolling terrain south of Hebron in the West Bank, which Israel has occupied since it was captured in the 1967 Middle East war.

He moved two large flat stones into the shade as seats, and we sat down in a patch of lush grass, kept alive in the harsh summer heat by water dripping from a pipe coming out of the spring. It was a small oasis at the foot of a steep, arid, rocky slope and the location, if not our conversation, felt peaceful in a way that the West Bank rarely does these days.

The conflict between Arabs and Jews for control of the land between the River Jordan and the Mediterranean Sea started well over a century ago when Zionists from Europe began to buy land to set up communities in Palestine.

It has been shaped by significant turning points.

The latest has come from the deadly 7 October 2023 attacks by Hamas and Israel’s devastating response.

The consequences of the last 22 months of war, and however more months are left before a ceasefire, threaten to spread across years and generations, just like the Middle East war in 1967, when Israel captured Gaza from Egypt and East Jerusalem and the West Bank from Jordan.

The scale of destruction and killing in the Gaza war obscures what is happening in the West Bank, which smoulders with tension and violence.

Since October 2023, Israel’s pressure on West Bank Palestinians has increased sharply, justified as legitimate security measures.

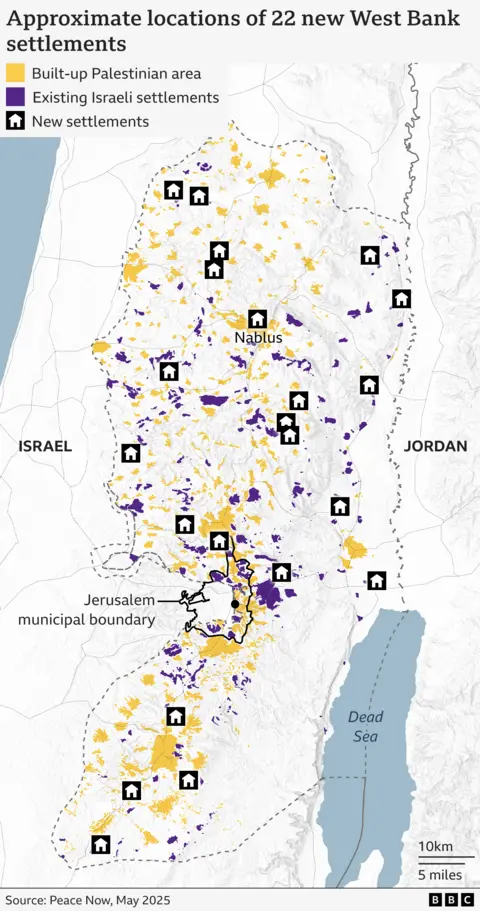

Evidence based on statements by ministers, influential local leaders like Simcha and accounts by witnesses on the ground reveal that the pressure is part of a wider agenda, to accelerate the spread of Jewish settlements in the occupied territories and to extinguish any lingering hopes of an independent Palestinian state alongside Israel.

Palestinians and human rights groups also accuse the Israeli security forces of failing in their legal duty as occupiers to protect Palestinians as well as their own citizens – not just turning a blind eye to settler attacks, but even joining in.

Violence by ultra-nationalist Jewish settlers in the West Bank has risen sharply since 7 October 2023.

Ocha, the UN’s humanitarian office, estimates an average of four settler attacks every day.

The International Court of Justice has issued an advisory opinion that the entire occupation of Palestinian territory captured in 1967 is illegal.

Israel’s rejects the ICJ’s view and claims that the Geneva Conventions forbidding settlement in occupied territories do not apply – a view disputed by many of its own allies as well as international lawyers.

In the shade of the fig tree, Simcha denied all suggestions he had attacked Palestinians, as he celebrated the fact that most of the Arab farmers who used to graze their animals on the hills he has seized and tend their olives in the valleys had gone.

He looks back to the Hamas October attacks, and Israel’s response ever since, as a turning point.

“I think that a lot has changed, that the enemy in our land lost hope. He’s beginning to understand that he’s on his way out; that’s what has changed in the last year or year and a half.

“Today you can walk around here in the land in the desert, and nobody will jump on you and try to kill you. There are still attempts to oppose our presence here in this land, but the enemy is starting to understand this slowly. They have no future here.

“The reality has changed. I ask you and the people of the world, why are you so interested in those Palestinians so much? Why do you care about them? It’s just another small nation.

“The Palestinians don’t interest me. I care about my people.”

Simcha says the Palestinians who left villages and farms near the hilltops he has claimed simply realised that God intended the land for Jews, not for them.

On 24 July this year, a panel of UN experts came to a different conclusion. A statement issued by the office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights said: “We are deeply troubled by alleged widespread intimidation, violence, land dispossession, destruction of livelihoods and the resulting forcible displacement of communities, and we fear this is severing Palestinians from their land and undermining their food security.

“The alleged acts of violence, destruction of property, and denial of access to land and resources appear to constitute a systemic pattern of human rights violations.”

Simcha has a plan to dig a swimming pool at the base of the spring where we sat to talk. Like many others who are leading the expansion of Jewish settlements in the West Bank, he is full of plans. When I met him first, not long after Hamas burst through Israel’s border defences on 7 October 2023, he lived in a small group of isolated caravans on a hilltop overlooking the Judean desert as it sweeps down to the Dead Sea.

Since then, Simcha says his community has expanded into around 200 people on three hilltops. He was part of the faction of the settler movement known as hilltop youth, a radical fringe that became notorious for the violent harassment of Palestinians. Most Israelis who have settled in the occupied territories are not like Simcha. They went there not for ideological and religious reasons, but because property was cheaper.

But now men like Simcha are at the centre of events, with their leaders in the cabinet, leading the charge, married, older, thinking not just about swimming pools for their children but of victory over the Palestinians, once and for all, and everlasting Jewish possession of the land.

Simcha comes across as a happy man. He believes his mission – to implement the will of God by turning the West Bank into a land for Jews, and not for Palestinians – is progressing nicely.

Israel’s decades-old project

Israel’s project to settle Jewish citizens in the newly occupied territories started within days of its victory in 1967. Over the last almost 60 years, successive Israeli governments and some wealthy sympathisers have invested vast amounts of money and energy to get to the point where around 700,000 Israeli Jews live in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem.

I have been watching the settlements grow for about half of the lifetime of the project, since I first reported from the occupied Palestinian territories in 1991. In that time, the terrain of much of the West Bank has been transformed. The bigger settlements look like small towns, and the West Bank is carved into sections by a network of roads and tunnels built by Israel that are as much about staking an immovable claim to the land as they are about traffic management.

On remote hilltops at night, you can see the lights coming from the caravans of settlers who see themselves as Jewish pioneers. Olive groves, orchards and vineyards owned by Palestinian farmers along the road network are often overgrown, sometimes dotted with piles of rubble left from buildings Israel has demolished.

Controlling the land around the roads is necessary, Israel says, to stop attacks on Jews in the West Bank.

Farmers in areas under settler pressure often need military permission to visit their land, sometimes just once a year.

Palestinian farmers going about their business in vans or on donkeys used to be a common sight. In many parts of the West Bank, you just do not see them anymore, especially in places like the settlements east of Shiloh on the road to Nablus, where small groups of shacks and caravans on hilltops have connected up into sprawling residential hubs linked by sinuous road networks.

When first I reported on settlements, Israeli leaders would often say that national security depended on them. Enemies lurked across the Jordan valley, and pushing out the frontier, building the land, was a Zionist imperative.

Just like the kibbutz movement of collective farms in the 1920s and 1930s inside present-day Israel, settlements in the occupied territories after 1967 were strategically placed as a first line of defence.

In this conflict, land is a vital commodity.

Trading land taken by Israel in 1967 for peace with Palestinians who wanted it for a state was at the heart of the Oslo peace process that ended in violence but provided a false dawn of hope in the 1990s.

There were headlines around the world when, after months of secret negotiations in Norway in 1993, there was a handshake on the White House lawn between Israel’s Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and the Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat. They had signed a declaration of principles that was hoped would lead to the end of the conflict. Israel would relinquish occupied land to Palestinians. In return, they would drop their claim to territory they had lost when Israel declared independence in 1948.

Cynthia Johnson/Liaison

Cynthia Johnson/LiaisonThe argument at the heart of their conflict across the 20th Century, about who controlled land they both wanted, would be solved by splitting it.

After a final disastrous summit at Camp David in 2000, the hopes of 1993 were replaced by the deadly violence of a Palestinian uprising and a massive military response from Israel.

Part of the reason why the peace process failed was that other forces, outside the talks, were at work.

Hamas never dropped its belief that the entire land of Palestine was an Islamic possession and used suicide attacks to discredit the notion that peace was possible.

Among religious Zionists in Israel, the victory in 1967 had supercharged a wave of messianism – the belief that a divine being was coming who would redeem the Jewish people.

It electrified the settler movement.

Rabin was assassinated in November 1995 by a Jewish extremist brought up in Herzliya on the Mediterranean coast who spent weekends at settlements in the West Bank. During his first interrogation by the Israeli security service, Shin Bet, he asked for a drink so he could toast the fact that he had saved the Jewish people from a disastrous path that denied the will of God.

Warning: This section contains an image some people might find upsetting

Today, the messianic idea grips settlers like Simcha more powerfully than ever.

They believe the victory in 1967 was a miracle granted by God, that restored to the Jewish people the ancestral lands that he had given them in the mountain heartland of Judea and Samaria – the area that much of the rest of the world calls the West Bank. Some believe events since 7 October have extended the miracle.

Last summer, the Minister for Settlements and National Missions, Orit Strock, put it like this to a sympathetic audience at an outpost in the Hebron hills, the area where Simcha operates.

“From my point of view, this is like a miracle period,” she said. “I feel like someone standing at a traffic light, and then it turns green.”

Minisyer Strock was speaking a few days before the ICJ issued its opinion.

She made her remarks at a settlement in the Hebron hills that the government had just “legalised”.

Israeli law distinguishes between “legal” settlements and “illegal” outposts – a distinction that is in practice being blurred by the government’s actions.

Outposts rebranded as “young settlements” are being retrospectively legalised as the government directs funds towards them.

Oren Rosenfeld/BBC

Oren Rosenfeld/BBCAt a ceremony in one of them in the south Hebron Hills in April this year, Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich, whose powers over the running of the occupation also make him something like the governor of the West Bank, donated 19 all-terrain vehicles to the settlers. He praised them for “grabbing massive territories”.

A sharp-eyed reporter at the Times of Israel pointed out that one of the settlers at the ceremony, Yinon Levi, had been filmed harassing Palestinians from an all-terrain vehicle. Levi is sanctioned by the UK and the European Union for using violence to drive Palestinians off their land, though President Trump lifted similar sanctions imposed by Joe Biden.

Levi is radical settler royalty, married to the daughter of Noam Federman – a notorious extremist. Federman is a former leader of the Kach party, which is designated as a terrorist organisation by Israel, the US, the European Union and others.

On 28 July this year, Yinon Levi fired a bullet that killed Odeh Hathaleen, a Palestinian activist and journalist, during a disturbance in the West Bank village of Umm al-Khair. Levi pleaded self-defence and was released after three days of house arrest.

When we went to Umm al-Khair, Hathaleen’s dried blood was still at the place where he was killed.

His brother, Khalil, told me the dead man was holding his five-year-old son, Watan, and filming the violent scenes on his phone when he was killed.

Oren Rosenfeld/BBC

Oren Rosenfeld/BBCThe settlement movement in the West Bank has powered ahead since 7 October, under the direction of hardline Jewish nationalists in the cabinet, men like Itamar Ben Gvir, the national security minister, and Bezalel Smotrich, who is Strock’s leader in the Religious Zionist Party.

Ben Gvir was not drafted by the IDF when he turned 18, because of his extreme beliefs. He claims he campaigned to serve.

The two ministers are very different people to the secular politicians – retired generals like Yigal Allon from the Israeli left and Ariel Sharon from the right – two men who drove the settlement movement forward in its first two decades after 1967.

Just like Allon and Sharon, they believe that security requires power.

But for Smotrich, Ben Gvir and their followers, that is underpinned by the certainty of religious belief.

The influence they have acquired in return for supporting Netanyahu and keeping him in power continues to frustrate and enrage secular Israel.

Smotrich’s Israeli opponents use the word “messianic” as term of abuse when they talk about him.

Allon and Sharon could be ruthless. After the 1967 war, Allon advocated the annexation of large parts of the West Bank and the Jordan Valley. Neither man believed they were doing the will of God.

Hamas uses religion to justify its violent opposition to the existence of Israel. Religious Zionists in the settler movement believe they are doing God’s will.

Belief in a direct connection with God does not guarantee war. But it makes the compromises necessary for peace hard to achieve.

‘Now the settlers are the military’

We arranged to meet Yehuda Shaul at the road junction next to Sinjel. He is one of Israel’s most prominent opponents of the occupation.

Shaul founded an organisation called Breaking the Silence after, as a soldier, he saw first-hand the inherently brutal realities of a military occupation that has lasted almost 60 years.

Fellow Israelis have branded supporters of Breaking the Silence, which he no longer leads, as traitors many times.

Israeli military crackdowns since the October attacks have reduced Palestinian violence against settlers, while settler attacks on Palestinians have grown sharply.

Shaul says that the line between settlers and the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) has become blurred.

The war in Gaza has required the longest mobilisation of military reservists – the backbone of the IDF – in Israel’s history. To get more Israelis into uniform, brigades in the West Bank have formed regional defence units made up of settlers.

“Now the settlers are the military. In the military are the settlers. So that settler on the hilltop nearby a Palestinian herding community that was beating them up and throwing stones for the past two three or four years, trying to get him out, now is the soldier or the officer in uniform with a gun responsible for the area.

“So when he comes to a Palestinian and says, ‘you have 24 hours to pack up and leave or I’m going to shoot you,’ the Palestinian knows there is nothing to protect him.”

Oren Rosenfeld/BBC

Oren Rosenfeld/BBCShaul believes Israel has two choices left. One direction, he argues, is “the vector that this government is writing, displacement, abuse, killing, destroying Palestinian life, ultimately, writing a vector to mass population transfer”.

“Or, it is two states where Palestine resides besides Israel and both peoples here have rights and dignity. These are the only two options in our cards. Now you and anyone who watches us, need to choose which one you support.”

He uses language about Netanyahu’s conduct of the Gaza war since 7 October that is rare in Israel but common among Palestinians and increasingly heard among Israel’s critics in Europe.

This is part of our conversation, in the shadow of the steel and razor wire between the village of Sinjel and Road 60 – the West Bank’s main highway.

He says: “I think while we see a war of extermination in Gaza… we see a massive campaign by the state and the settlers… to basically ethnically cleanse as much land of the West Bank from Palestinians.”

I reply: “Of course, if Netanyahu was here, any of his supporters, they’d say, ‘what a load of rubbish. This is about Israeli security against terrorism and attacks on Jews.’ What do you make of that?”

He responds: “I actually believe that if 7 October taught us one thing it is, if you really care about protecting Israelis and Palestinian life, you need to take care of the root causes of the violence: decades of brutal military occupation, displacement of Palestinians and a conflict that is going on for about 100 years.

“Ultimately, the security protection, the sustainability of Jewish self-determination in this land, is interlinked and intertwined with achieving self-determination rights and equality for Palestinians.”