BBC Scotland News

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCats develop dementia in a similar way to humans with Alzheimer’s disease, leading to hopes of a breakthrough in research, according to scientists.

Experts at the University of Edinburgh carried out a post-mortem brain examination on 25 cats which had symptoms of dementia in life, including confusion, sleep disruption and an increase in vocalisation.

They found a build-up of amyloid-beta, a toxic protein and one of the defining features of Alzheimer’s disease.

The discovery has been hailed as a “perfect natural model for Alzheimer’s” by scientists who believe it will help them explore new treatments for humans.

Dr Robert McGeachan, study lead from the University of Edinburgh’s Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies, said: “Dementia is a devastating disease – whether it affects humans, cats, or dogs.

“Our findings highlight the striking similarities between feline dementia and Alzheimer’s disease in people.

“This opens the door to exploring whether promising new treatments for human Alzheimer’s disease could also help our ageing pets.

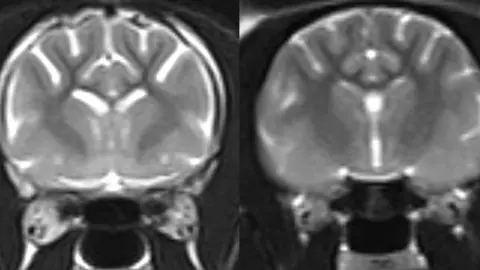

Microscopy images of older cats which had previously shown symptoms of feline dementia revealed a build-up of amyloid-beta within the synapses – the junctions of brain cells.

University of Edinburgh

University of EdinburghSynapses allow the flow of messages between brain cells, and losing these causes reduced memory and thinking abilities in humans with Alzheimer’s.

The team believe the discovery in cats could help them get a clearer understanding of the process, offering a valuable model for studying dementia in people.

Previously, researchers have studied genetically-modified rodents, although the species does not naturally suffer from dementia.

“Because cats naturally develop these brain changes, they may also offer a more accurate model of the disease than traditional laboratory animals, ultimately benefiting both species and their caregivers,” Dr McGeachan said.

Will this research benefit cats?

The researchers found evidence that brain support cells – called astrocytes and microglia – engulfed the affected synapses.

It’s known as synaptic pruning, an important process during brain development but which contributes to dementia.

Prof Danielle Gunn-Moore, an expert in feline medicine at the vet school, said the discovery could also help to understand and manage feline dementia.

“Feline dementia is so distressing for the cat and for its person,” she said.

“It is by undertaking studies like this that we will understand how best to treat them. This will be wonderful for the cats, their owners, people with Alzheimer’s and their loved ones.”

The study, funded by Wellcome and the UK Dementia Research Institute, is published in the European Journal of Neuroscience, and included scientists from the Universities of Edinburgh and California, UK Dementia Research Institute and Scottish Brain Sciences.