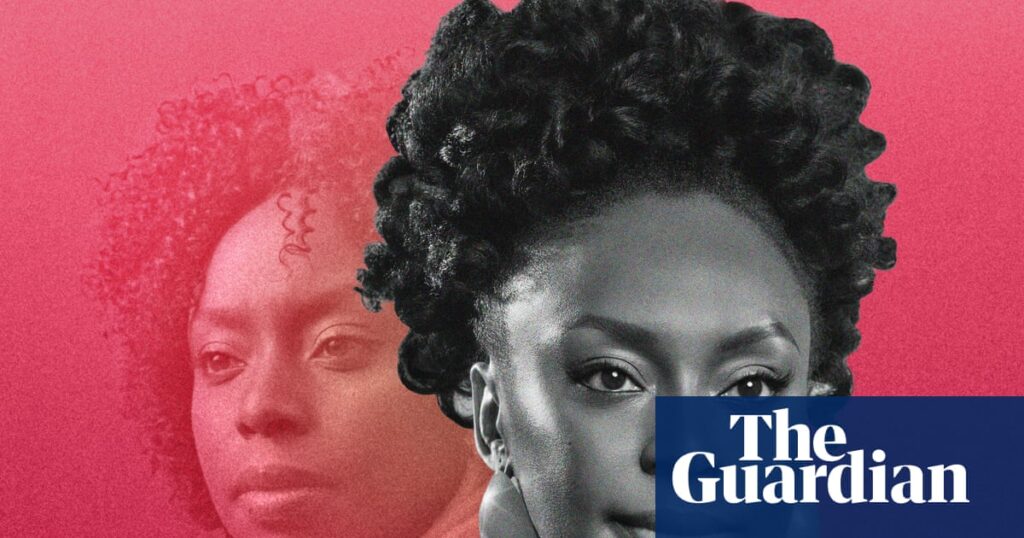

It’s summer reading time, and I have finally dived into Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Dream Count, her highly anticipated return to fiction after a 12-year hiatus. This week, I give a review of sorts – what was most striking about the work is how it feels of a certain time, and how Adichie is an icon who sits between two eras.

Feminist icon to pop culture artefact?

Dream Count is as much a book as it is a publishing event. In the years between her previous novel, Americanah – a book so successful that it has made the New York Times’s list of the best fiction of the 21st century – and her latest offering, Adichie became a cultural figurehead. Dream Count returns to the themes that Adichie is in greatest command of: an existence that sits between living in Africa and living in the diaspora. The Covid pandemic acts as a backdrop to the lives of four female protagonists, and between them there are the roiling affairs of the heart, disappointments and assaults and bodily wreckage whose collective toll starts to be felt, or “counted”, in middle age.

The central figure is modelled on Nafissatou Diallo, who was allegedly assaulted in 2011 in a hotel room by the French economist Dominique Strauss-Kahn. It is a “gesture of returned dignity”, Adichie says in her author’s note. But it is also an example of how the author always leans into the sharp and jagged realities of womanhood, with no desire to smooth its edges. Adichie is, above all, a a matter-of-fact narrator of bodily ravages: bad sex, small penises, postpartum injuries, fibroids and heavy bleeding. This is my favourite quality of Adichie’s. She doesn’t traffic in banalities or idealisation of Black women as poetically and magically tragic or noble. They just are.

In Dream Count, Adichie’s style is as confident and singular as ever. Almost too much so. Her strong voice inserts itself into the mouths of her protagonists, who sometimes pronounce things that only she writes, rather than what regular people say: “Each day with Chuka,” one character narrates, “I encountered his otherness.” Ultimately, the reader always feels in safe hands. This novel is about intersecting female relationships in a female universe of voices and points of view, and there is something cosy and mutually affirming in that.

Yet it also feels artificial (which is the writer’s prerogative, after all, to construct their narrative world), as if these characters were performing some grand allegory of a woman’s arc. I found myself thinking: just let them speak! Just let me embrace these women you have so tenderly portrayed. Which brings me to my main sense of the book: it felt like a series of set pieces, rather than a coherent work of fiction; an extended commentary on gender relations and societal expectations of women. I didn’t feel carried along, more an audience to strong but disconnected accounts and introspections.

There is something in this that may be related to the moment that transformed Adichie from a literary sensation to a pop culture behemoth. Her book-length essay We Should All Be Feminists, a landmark treatise on, well, why we should all be feminists, became a totem of a particular era of mid-00s trends. It was the time of Lean In and Girl Bosses and a broader fourth-wave feminism that revived the movement through online activism, #MeToo, and women’s marches.

Audio excerpts from Adichie’s Ted Talk on feminism were picked up by Beyoncé and featured in her 2013 hit Flawless. Dior designed T-shirts with “We should all be feminists” printed on them. It was a weird time. Adichie was a perfect icon for that moment: strident, smart but also glamorous – marrying liberal progressive politics on gender with accessibility. She became the face of the beauty brand No 7, was on Vanity Fair’s best-dressed list, and embraced fashion and beauty as a rebuke to those who see them as somehow diminishing women’s intellect.

after newsletter promotion

Adichie distanced herself from Beyoncé’s version of feminism in particular, “as it is the kind that … gives quite a lot of space to the necessity of men”, she said. But there is an echo of that time and its ensuing discourses in Dream Count, even as she tries to transcend it. Men are not the protagonists but are still somehow centred, even if we roll to a conclusion that perhaps they are not necessary. And there are on-the-nose statements where Adichie ventriloquises through characters that tone of clapback feminism. “Dear men,” writes one of her characters in her blog where she dispenses satirical advice to men, “I understand that you don’t like abortion, but the best way to reduce abortion is if you take responsibility for where your male bodily fluids go.” There are also jarringly cartoonish portrayals of American, or Americanised, characters opining, which I interpreted as a jab at the smugness of “woke” progressives, a cohort I suppose Adichie would like to distance herself from.

The overarching feeling was of a book that was smaller than its writer. Adichie, as a talent, remains sharp and masterly, but as a social and political commentator, she sounds stranded. Perhaps one of the dangers of being an icon is the risk of one day becoming an artefact.