BBC News Arabic

BBC

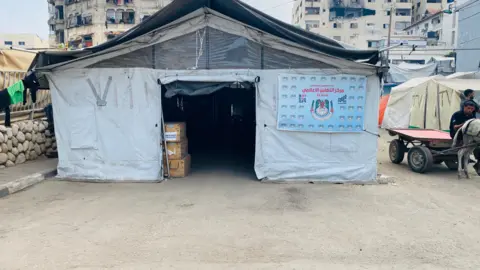

BBC“I never imagined that one day I would be living and working in a tent, deprived of the most basic human necessities – even water and a bathroom.

“It’s more like a greenhouse in the summer and a refrigerator in the winter,” journalist Abdullah Miqdad told the BBC.

After 22 months of war in Gaza, most journalists find themselves working in tents around hospitals in order to access the electricity and reliable internet connection they need to do their jobs.

Power has been cut off across Gaza, so hospitals, whose generators are still functioning, provide the electricity to charge phones and equipment, and offer high points with better mobile reception.

But working at hospitals has not afforded them safety, with Israeli strikes on hospitals and their compounds killing a number of journalists during the conflict.

On Monday, five journalists were among at least 20 people killed in a double Israeli strike on Nasser hospital in the southern city of Khan Younis.

International news outlets, including the BBC, rely on local reporters within Gaza, as Israel does not allow them to send journalists into the territory except on rare occasions when they are embedded with Israeli troops.

‘As journalists, we feel we are targeted all the time’

At least 197 journalists and media workers have been killed since the war in Gaza began following the Hamas-led attack on Israel on 7 October 2023 – 189 of them Palestinians killed by Israel in Gaza, according to the US-based Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ).

Ahed Farwana of the Palestinian Journalists Syndicate in Gaza told the BBC that he and his colleagues felt targeted by Israeli forces “which leaves us in constant fear for our own safety and that of our families”.

After nearly two years of war, journalists are exhausted from non-stop work, but demand for news coverage persists.

This has opened the door for young people in Gaza, some of whom had never worked in journalism before, to become reporters and photojournalists.

Some journalists work officially for local or international media outlets, but many are hired on temporary contracts. This means their employment is less predictable and the protective equipment, insurance, and resources they receive varies greatly.

“Every journalist in the world has the right to enjoy international protection. Unfortunately, the Israeli military does not treat journalists this way, especially when it comes to Palestinian journalists,” Ghada al-Kurd, a correspondent for German magazine Der Spiegel, told the BBC (for which she also sometimes works).

EPA, AP, Reuters

EPA, AP, ReutersIsrael has repeatedly denied that its forces target journalists.

However, the Israeli military said it did target Al Jazeera correspondent Anas al-Sharif in his media tent in Gaza City on 10 August, in a strike that also killed three other Al Jazeera staff, two freelancers, and one other man. The military alleged Sharif had “served as the head of a terrorist cell in Hamas”, which he had denied before his death.

The CPJ said Israel had failed to provide evidence to back up its allegation, and accused Israeli forces of targeting journalists in a “deliberate and systematic attempt to cover up Israel’s actions” in Gaza.

Reuters cameraman Husam al-Masri was killed in the first strike on Nasser hospital on Monday. The second strike, minutes later, killed rescue workers and four other journalists who had arrived at the scene – Mariam Abu Dagga, a freelancer working with the Associated Press; Al Jazeera cameraman Mohammad Salama; freelance journalist Ahmed Abu Aziz and freelance video journalist Moaz Abu Taha.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu described the incident as a “tragic mishap”.

The Israeli military said on Tuesday that, after an initial inquiry, “it appears” troops struck “a camera that was positioned by Hamas in the area of the Nasser Hospital that was being used to observe the activity of [Israeli] troops”. It also identified six people whom it said were “terrorists” killed in the strikes. None of the five journalists were among them.

The military provided no evidence and gave no explanation for the second strike.

“When you’re working inside a tent, you never know what might happen at any moment. Your tent or its surroundings could be bombed – what do you do then?” says Abdullah Miqdad, who is a correspondent for Qatar-based Al-Araby TV.

“In front of the camera, I have to be highly focused, mentally alert, and quick-witted despite the exhaustion. But the harder part is staying aware of everything happening around me and thinking about what I could do if the place I’m in is targeted,” he told the BBC.

‘We ourselves are hungry and in pain’

Last Friday, famine was confirmed in Gaza City for the first time by a UN-backed body responsible for monitoring food security.

The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) reported that more than 500,000 people in the Gaza Strip were facing “starvation, destitution and death”.

The journalists in Gaza are suffering the same extreme hunger as those they are covering.

“A cup of coffee mixed with ground chickpeas, or a glass of unsweetened tea, might be all you can consume during an entire workday,” says independent journalist Ahmed Jalal.

“We suffer from severe headaches and fatigue, unable to walk from the sheer hunger,” he told the BBC, “but we still carry on with our work.”

Ahmed has been displaced many times with his family, yet each time he has continued his journalistic work while trying to secure food, water and shelter for his family.

“My heart breaks from the intense pain when I report the killing of fellow journalists, and my mind tells me I might be next… The pain consumes me inside, but I hide it from the camera and keep working.”

“I feel suffocated, exhausted, hungry, scared – and I can’t even stop to rest.”

‘We have lost the ability to express our feelings’

Ghada Al-Kurd

Ghada Al-KurdGhada Al-Kurd says two years of covering news about death and hunger has changed her.

“During this war, we have lost the ability to express our emotions,” Ghada told the BBC. “We are in a constant state of shock. Maybe we will regain this ability after the war ends.”

Until that day comes, Ghada holds back her fear for her two daughters and her grief for her brother and his family, whose bodies she believes are still buried under rubble following an Israeli strike in northern Gaza early in the war.

“The war has changed our psyches and personalities. We will need a long period of healing to return to who we were before 7 October 2023.”

Photojournalist Amer Sultan in Gaza assisted in preparing the report.