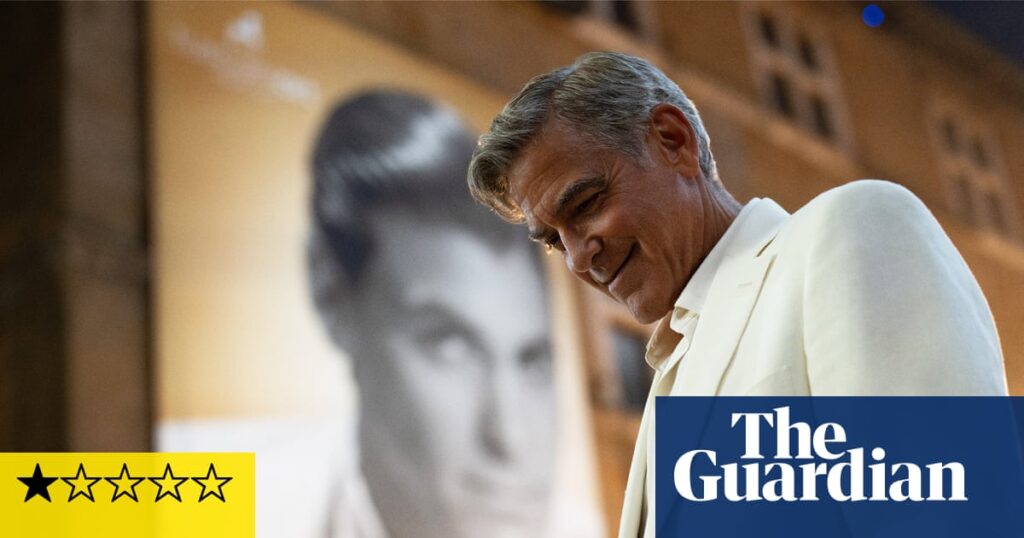

Everybody loves George Clooney, and rightly so. His performances in films such as Michael Clayton, Out of Sight and Ocean’s Eleven have been a joy, and as an elegant public figure he has more or less single-handedly underwritten the continuing currency of Hollywood classiness. But in this dire, sentimental and self-indulgent film, he has the look of a man who has found strychnine in his Nespresso pod and can’t remember which of the cupboards in his luxury hotel suite contains the antidote.

It is directed by Noah Baumbach, whose 2022 film White Noise, based on the Don DeLillo novel, was a superb competition entry at Venice. (Baumbach was reportedly disconcerted by a tepid response; I thought it was brilliant.) But this one is a grisly, sucrose, sub-Fellini swoon on the subject of a super-handsome Hollywood actor attending a Italian arts festival to accept a lifetime achievement award, and naturally experiencing endless bittersweet flashbacks to his youth, in which the middle aged Jay Kelly looks on, with that knowing Clooney smile.

The reason for attending this festival is so that Kelly can bump into his teenage daughter who is backpacking around Europe. He even takes the humble train so he can hang out with her, and thereby encounters an uproarious array of picturesque and ordinary people, including a hyperactive German cyclist played by Lars Eidinger.

And at this moment of midlife self-examination, Kelly feels that he has let everyone in his life down (although bafflingly the mother of his grownup children has gone missing from the story). He is estranged in serious and non-serious ways from his daughters (played by Riley Keough and Grace Edwards), he is preparing to betray his longsuffering agent Ron (Adam Sandler), he has refused to help his directorial mentor (Jim Broadbent) and he is plagued with memories of how at the beginning of his career he ruthlessly stole a key part from his more talented drama school pal (Billy Crudup), whose career went downhill afterwards. And he can’t decide who he is, or if there is any one behind the celebrity mask.

So Baumbach’s film pirouettes into territory already trodden by Fellini’s 81/2 and Woody Allen’s Stardust Memories, but smothers everything in a bland, Tuscan sunshine-syrup. The sharp realisations about the cruelty of show business are cancelled by gushes of Hollywood self-adoration and self-forgiveness and jokey non-comedy.

Finally, Kelly watches a sizzle-reel of his roles at the festival ceremony, and of course these are clips of Clooney’s actual films (no ER though). It is an unbearable imposition on the audience’s affections, but there is a tear in Jay’s eye. Cine-narcissism like this is always tiresome, and it isn’t any more palatable in a European setting.