You made it time. If you want to look a little longer, just scroll back up and press “Continue.”

So, imagine it. Venice in 1908. Beautiful, right?

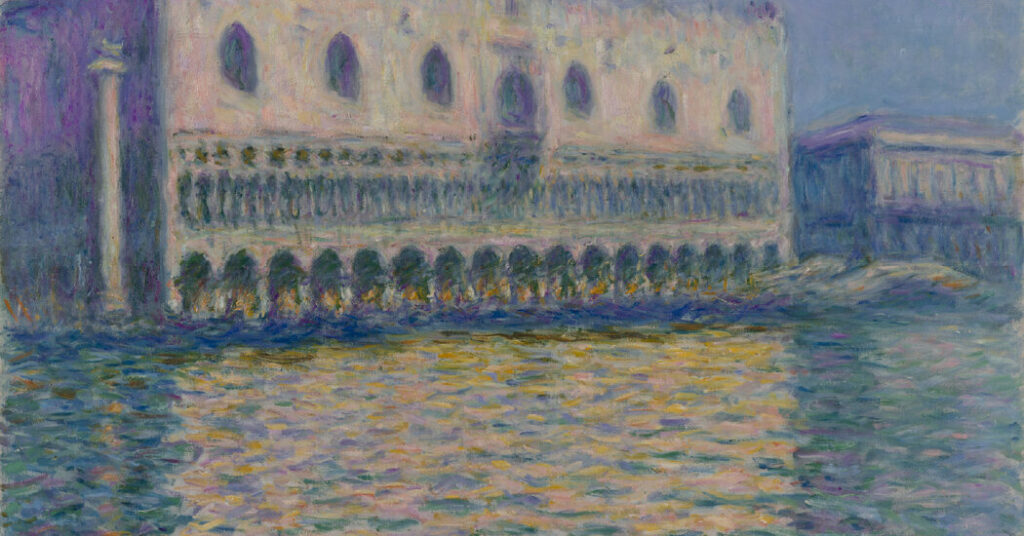

Floating in a gondola in the lagoon facing the Doge’s Palace, Claude Monet was annoyed. The gondoliers had tried three times to find the spot he’d been painting from, but couldn’t.

“He gave up on the session and returned to the hotel absolutely furious and regretful,” reported his wife, Alice, who accompanied him on the one and only trip he made to the city of water.

Monet — the famed painter of haystacks and water lilies, who had revolutionized art decades earlier with his impressionistic scenes of color, light and reflections — was furious? Regretful? Whoa.

But it wasn’t all misery. On another day, Alice wrote: “I am happy here to see Monet so full of ardor, and doing such beautiful things and, between us, other than the endless water lilies, and I believe that it will be a great triumph for him.”

Much of this will be laid out starting Oct. 11 at an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, “Monet and Venice.” The painting you just spent time with is at the center of the show. Lisa Small, the museum’s senior curator of European Art, walked me through it.

For a man obsessed with light and water, a visit to Venice would seem like a foregone conclusion. But Monet didn’t want to go. He was in his late 60s. He didn’t want to leave his garden in Giverny in northern France, where he had been toiling away on his water lily series. And, anyway, he said that Venice was “too beautiful to be painted.”

Ms. Small said: “Venice is like the prototypical city motif — you’re not going to find anything. There is no off the beaten track in Venice. All tracks are beaten.”

John Singer Sargent had painted it a few years before Monet:

James McNeill Whistler made etchings in the late 1800s:

And in 1750, the Venetian painter Canaletto captured his hometown in exhaustive detail:

But Alice wanted to go and Monet eventually relented. They arrived and posed for photographs in the Piazza San Marco with the pigeons:

Monet couldn’t resist Venice’s charms for long. He stayed for two months; had canvases and supplies sent to him; and made 37 paintings, including a few versions of “The Doge’s Palace.”

It wasn’t easy. Fighting the weather and deep self-doubt, Monet seemed to be up as often as he was down.

“I’m sure there are nicer words I could use, but oh my God, he was a whiner, a complainer,” Ms. Small said. “It’s something that I didn’t really realize myself even about him until I really delved into this.”

One of these works, painted from a gondola, is this view of the Doge’s Palace:

The doge was the head of state in the Venetian Republic. The palace was the center of government for centuries.

This scene would have been crowded with people and all manner of watercraft, Ms. Small said, but Monet edited all of that out. “The palace,” Monet wrote, “was just an excuse for painting the atmosphere.”

“It offered him all of the things that he was looking for in a motif the same way on another day a haystack would,” Ms. Small said. “In the end, it’s architecture in the light under the sun, right?”

The hazy atmosphere he built on the canvas is made up of countless strokes and swishes of color. Just look at the water:

“The water isn’t just blue,” Ms. Small said. “It’s yellow. It’s green. It’s not blue at all, actually.”

A line of gondolas at the base of the palace is rendered with swoopy blue curves:

The shadows here aren’t black, they’re purple (and blue and beige and yellow and green):

The colors might not seem as if they make sense up close. To understand, it helps to look at a color wheel (and talk to an expert). I called Alan Roberts, a longtime painting teacher and the director of the Leo Marchutz School of Painting & Drawing in Aix-en-Provence, France. Mr. Roberts started from the top.

(This may seem basic, but if you think color is easy, walk through the paint aisle at Home Depot and look at the agony on couples’ faces.)

Complements, if used correctly, really help a painting (or a living room wall, or an outfit) come to life.

You’ll notice there’s no black on the wheel, or really in Monet’s painting. The next time you’re in an Impressionists’ wing, look around; you’ll see very little pure black. The artists rendered shadows full of color, often using the complements of the lighter colors.

Now look back at the painting with this in mind. Take the left corner of the palace here where light and shadow meet:

The complement of the warmish yellow color is the coolish purple used here as its shadow. If you look closely, there are all three complementary pairs at work.

Compare that with this detail of the Canaletto painting we saw earlier:

Canaletto was painting in a different time, nearly a century before the invention of photography. He had different aims. The shadows, edges and ornamentation are rendered here in hyper detail. By Monet’s time, photography was common and painting had changed (in part because of him).

“What Monet and the Impressionists continue to give us is a kind of hand gesture; you feel close to the maker,” Ms. Small said. “In every stroke of paint you have the sense of their hand moving, of them holding the brush and laying that little bit of yellow right next to that little bit of blue.”

Zoom into the palace’s reflection in Monet’s water, and complementary relationships are everywhere: dabs of warm red with cool green, purples and yellows, blues and oranges, all dancing together.

When these opposite colors are placed next to each other, it creates tension. The tension makes the whole picture feel more vibrant. It simulates the effects, for example, of light on water that never stops moving.

“You’ve got green and red, yellow and purple, and blue and orange, over every square inch of the painting, working all the time,” Mr. Roberts said.

Monet is using his color and brushstrokes to describe the character of the represented objects, Mr. Roberts said. His water looks wet. His sky looks airy. His stone looks solid.

The brushstrokes may feel dashed off and effortless, but Monet labored over these paintings. He started them outside in Venice, then brought them back to his studio in Giverny and worked on them as a series.

“He was grappling with this paradox,” Ms. Small said. “He always wanted to capture an instant — the moment that the light flickered on the water in this very specific way, under these very specific lighting conditions — but it took him a really long time.”

After the trip to Venice, and his work on the water, Monet returned to the place he knew best: his own garden in Giverny, home to the famous pond with water lilies.

“He went to Venice and he had this experience, surrounded by water, where he was both enchanted and frustrated every hour of every day,” Ms. Small said. “And he came back and he said my trip to Venice has made me see my paintings with a fresh eye, with a new eye, and I am ready to move ahead with my water lilies show.”

The show, in 1909, was groundbreaking. It debuted Monet’s paintings of water lilies that focused only on the surface of the pond — boundless water. The New York Times said the paintings were “the latest statement of a genius that has won the right to be called monumental.”

Spending some time with Monet may give us fresh eyes as well. Squint when you look at the shadows today. You may not see the complements right away, but keep looking.

Monet and Venice opens at the Brooklyn Museum on Oct. 11.

This is an installment in our series of experiments on art and attention. Sign up to be notified when new installments are published here. And let us know how this exercise made you feel in the comments.