Among the many men and women of the hour during this weekend’s Telluride Film Festival in Colorado, Ethan Hawke was soaring arguably higher than even some the other featured guests, due to having two very different films in the program, one a directorial effort and the other an awards-attention-attracting starring role. He also received a Telluride medallion and tribute as part of the festivities — a moment of triumph that stands at odds with some of the tougher times experienced by the two musical figures who are the subjects of his respective films, “Highway 99: A Double Album,” his documentary about country great Merle Haggard, and “Blue Moon,” which has him starring as the great lyricist Lorenz Hart.

As proof of just how fearless he is, Hawke ventured into what some would consider the very hub of the festival, the Baked in Telluride walk-in eatery, to meet the press, as onlookers happily looked on from a distance with their pizza slices. Hawke talked with Variety about the happy coincidence of having two such estimable film biographies premiering at once in the mountain town, one of his own direction and one in which he stars for director Richard Linklater in a role that has already gotten him Oscar attention.

Hawke may not have picked the place to meet by accident, being a Telluride veteran. He first came to the festival in 2015 with his first directorial effort, “Seymour: An Introduction,” a doc about pianist Seymour Bernstein; he then returned as the star of Paul Schrader’s “First Reform” and the director of his daughter Hawke as Flannery O’Connor in “Wildcat.” Now, he’s gotten to premiere his fourth and fifth films here in one swoop — although “Highway 99,” which runs more than three hours with an intermission, had more limited showings and necessarily turned passholders away. “Blue Moon” comes out this fall, while the Haggard doc is just starting to go after acquisition, having just been finished.

How was it, getting the tribute on the first day of Telluride and having premieres for both of your new movies? You said Richard Linklater called it “Ethan Hawke Day.” Did it feel like a holiday was being created for you?

I had to wake up this morning and be like, “Ethan Hawke Day’s over.” So sad. But I love this festival, and to have these two different parts of my life be represented here feels really cool.

It has to be pretty coincidental that you’re at the festival with two films, one a starring vehicle and one a directorial effort.

Oh, it’s weird. I’m here with two films about two of the great American songwriters, which is kind of interesting. It’s not purposeful at all.

The Merle Haggard documentary has been about two years of work for you, and the Lorenz Hart biopic is fresh but in some ways… how long has it been since it was first brought up, again?

Rick and I have been talking about making “Blue Moon” for 12 years, and we’ve slowly kind of worked on this and developed the script. Every 18 months or two years, we’d take it out and do a reading in my apartment or somewhere else and and think about it. And then finally, I don’t know, 18 months ago or something, it was “I think we’re ready. Let’s make this thing.” And I thought we were ready for years.

Linklater is the ultimate “I will make no film before its time” guy.

It’s really inspiring. I mean, 99% of directors, if they had a great script that they thought one of their favorite actors was 10 years too young for, they would just cast someone else. They wouldn’t say, “I’ll wait 10 years.” Who does that?

You couldn’t be at a single festival with two movies that are less alike in most ways, and yet…

For me, they’re really in absolutely separate boxes. “Blue Moon” is Rick and I are trying to do what we’ve done our whole lives, but trying to grow up. The level of difficulty on this was… we both felt that we kind of reached the wall of our talent. Like: this is really hard to do. It’s gonna require a lot of what we’ve learned, if not everything. And then the Merle thing… The documentary space is a space where I’ve learned to create balance in my life, because it’s such a long-form medium; you work on it for years, going through the archival. And it gives me something to do when I’m out of work as an actor that I really enjoy and have a passion for. And I love music, from playing Chet Baker (in 2015’s “Born to Be Blue”) to playing Lorenz Hart, to directing the “Blaze,” movie. I’ve had a lot of experience around musicians, and it’s a secret language that moves me tremendously. So with these two films, one is my own personal box, and the other is this lifelong collaboration with Linklater. And they are both about songwriters, but it’s kind of reaching in a way (to compare them) because they’re total different parts of my brain.

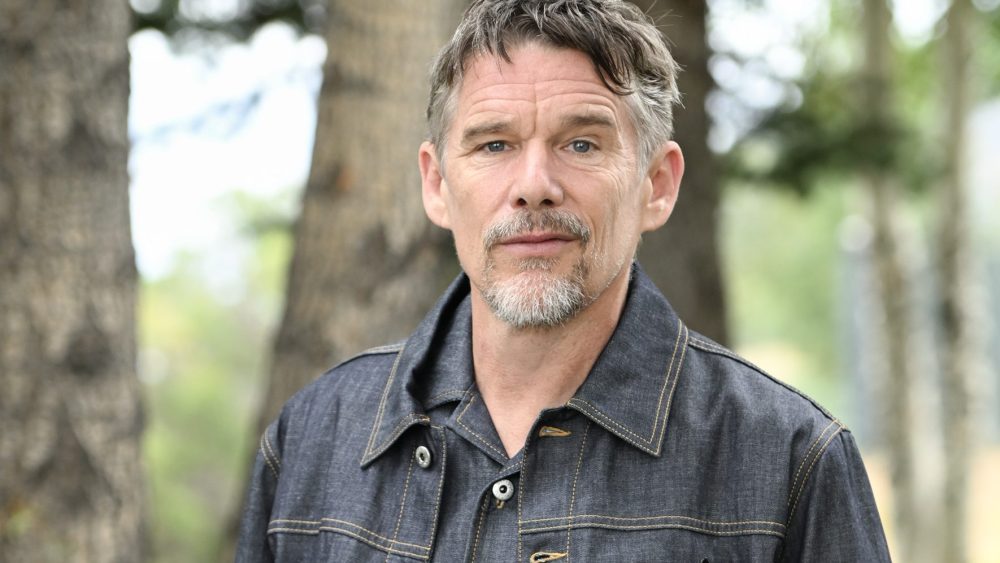

Ethan Hawke at the Telluride Film Festival

Chris Willman/Variety

Just thinking of Merle Haggard and Lorenz Hart as characters, though — do you think they have any similarities?

They’re both in tremendous pain, and I do think the songs spring (from that). I mean, you see Merle’s face when he’s talking about something that is hurting him and he’s trying to express it his whole life — anger, confusion, sadness, loss. Then there’s a period where addiction is obscuring whatever that initial wound is. And Larry Hart, the pain is there, too. They’re very different men, clearly, but there’s something about the longing to express themselves, to heal themselves… In playing Larry Hart, that’s where his pride lives. He almost has no dignity except in these songs. And he’s losing Richard Rodgers. It’s like the last piece of his self-esteem is being taken away. And I think “Blue Moon” is a story of a human being who died of a broken heart.

We want to talk about both of these movies individually, so let’s start with the Haggard movie, which is the one that kind of came as a surprise, since there was really no publicity about it at all before this last week. I looked up what was written about “Highway 99” prior to it being announced for Telluride a few days ago, and all there was was a few reports from Bakersfield news media in early June that you were shooting some things there with members of the Haggard family. So not only was it secret, but we know you were still filming less than three months ago.

It was our little secret project, and you’re never sure how long you’re gonna work on a documentary. And I went to Bakersfield this summer and I thought I found the movie, and then it kind of quickly (accelerated). I had this amazing editor, Barry Poltermann, who cut “The Last Movie Stars” with me (Hawke’s six-hour miniseries about Paul Newman and other film acting greats. He’s a staggeringly talented guy, and all of a sudden we cracked it, and I was like, “I think this movie might be done. I mean, we could work on it another 10 years. I can get 10 more (contemporary) musicians. But it’s already too long.” I found the way to tie it together, and I sent it to Telluride and they said, “Yeah, we’d love to show it.” So I was like, all right, let’s finish!

And were you brought in by Jason Fine, the Rolling Stone magazine guy who has really moved into documentaries so much?

Jason is a friend of mine. I wrote this piece on Kris Kristofferson for Rolling Stone about 16 years ago, and Jason was my editor, and we just got along like a house on fire about country music. After he saw “The Last Movie Stars,” he took my wife and I out to lunch and was like, “I really think Merle deserves a serious documentary, and I think it’s a giant error in our national dialogue that we’re not looking at him.” And so we just started talking about what it would be, and all of a sudden I started to see it.

The election was coming up, and I knew that no matter who won, half the country was gonna be powerfully upset. So I thought it might be a perfect time to visit somebody who’s a non-dualistic thinker like Merle Haggard. He didn’t think in terms of left or right, he just thought in terms of human beings, and they could be left and they could be right. And I thought that he could be a really healing subject to study right now, to get us all thinking not oppositionally.

I can relate, because I once interviewed Haggard for a book on country music and politics, and I did an entire chapter just on him, trying to explore the mysteries of why people thought he was conservative if they were conservative and liberal if they were liberal. I called the chapter on him “Deep Purple.”

So you know exactly what I’m saying. Yeah, I wanted to make a deep purple movie. That’s exactly the point I came to. When you start putting the songs next to each other, you’re like: This guy’s not the voice of the silent majority. And he’s no hippie. I mean, he’s not Willie. But he’s not Nixon either. When I went to his house, he had met basically every president from Nixon forward, and the only one he had a picture of on his wall was Jimmy Carter — and I think he just liked him because he was a farmer. But anyway, what your chapter was is the same thing that motivated me to focus on it.

In the press notes you say that you did sort of worry a little about doing a Haggard doc at the start because of the difficulty you thought people might have in getting past preconceptions they have left over from his biggest song, “Okie from Muskogee.” I know from my own research, and from talking with him about it, that he had about 10 different explanations for that song.

And as I went over the archival of all the interviews he’s given about that, what he says about it changes constantly. I don’t think he really knew. And I think that’s the genius of the song, that he was writing what his father would think about the hippies — that’s what I think he was doing — and then he didn’t ever want to say it’s a joke song, because he’s writing about his father’s point of view. Why would he disrespect his father’s point of view? And the fucking song was a hit for three years, you know? It is weird, though, that one of our greatest songwriters’ most famous songs is a joke song. That’s the other reason why I wanted to make the documentary. He’s a great writer. “Mama’s Hungry Eyes” is a flat-out masterpiece…

Ethan Hawke at the Telluride Film Festival

Chris Willman/Variety

Country fans can spend a lot of time thinking about who’s the greatest of all time among the major figures who were singer-songwriters, and at any given point in your thinking it could be Willie or Dolly or Loretta. But then you come back to Merle just in terms of, of great singer, great picker, and the longevity of his poetry. Cash wrote a lot of great songs, but his output there was not that sustained, if you’re counting that as a factor.

And Willie’s a great songwriter, but he didn’t have the output that Merle did. And Dolly said … you know, in documentaries sometimes people say amazing things, but they take too long to say them, and you have to think what the value-per-second is. But Dolly said this amazing thing about Merle: she said it was almost unfair that he was such a good guitar player. She said he always hired a better guitar player than him. She thought he was second only to Hank Williams as far as a writer. And he had a voice that is debatably better than George Jones’. She said the only thing he didn’t have is: “He wasn’t an entertainer,” she said, “and Willie, Waylon, Johnny, myself, we were entertainers, and we knew how to brand ourselves and we knew how to pick a lane and kind of sell that lane.”

And that Merle’s’struggles with depression were so serious that he saw that as so phony. I mean, he told Dolly, “You’re a great musician. Why are you doing that silly TV show?” She’s like, “Well, I want to.” He would rather die, you know? It’s like he had everything but the showman piece. I mean, he could jam up there on stage, and he could entertain, but he didn’t like wearing cowboy hats. He’d walk out in a down vest, sneakers…

You make the point he was especially not into branding himself an outlaw. In subsequent decadess, so many country stars have done that, whether they ever spent a day in jail or not.

I know, and he could’ve looked it, but he didn’t. He didn’t want to join the Highwaymen just for that reason. He didn’t want a brand. He thought that was corny, that it was a lie. Cash said this thing, too, that didn’t make the doc; Cash said, “Merle Haggard is the person I’m pretending to be.” Isn’t that great?

Ethan Hawke in ‘Highway 99’

Courtesy Cinetic

There is a subtitle in “Highway 99: A Double Album” that we get to see and hear play out on screen. You have sides of vinyl pop up on screen with the 30 or so contemporary cover songs you commissioned people to come in and do acoustically for you — people from Dwight Yoakam and Norah Jones to Los Lobos and Taj Mahal to Sierra Ferrell, Jason Isbell, Sturgill Simpson and Tyler Childers. These contemporary performances give movie some dynamics, but also thematically, the song choices are important in setting up the sections that follow.

I’m trying to tell his life story with his own work, letting his work speak for itself. I wanted the movie primarily to be about songwriting, and when you listen to somebody cover a song, you kind of listen to the writing of the song in a different way. I always think that you can tell a great song by the ones that get covered and have different interpretations. And I also thought it would be a way to look forward as well as backward. You know, if you’re looking at Charley Crockett, you’re looking at the future of country music, or if you’re looking at River Shook, you’re looking at Valerie June. Put in any of these people and it helps it not be just like a time capsule. Let’s talk about the ‘70s, let’s talk about the ‘60s, but we’ll talk about it in reference to what that means to us today. That’s what I thought — it would keep bringing us back to 2025.

Two practical questions about releasing things: Is the movie up for sale right now? And do you foresee all these great covers being on a soundtrack?

We showed the film for the first time to anybody Friday night in Telluride. That’s the first time anybody who wasn’t working on the movie saw the movie. My hope is that we can find somebody to release it, and then the soundtrack will… In fact, I could get into really working on that. Shooter Jennings is such a good producer. I’d kind of like to get everybody back and let him really produce (studio versions), actually. Because I didn’t want in the movie for it to be a dueling thing of whose cover is better. I just wanted it to be about the song, so we tried to do it as simply as possible. But for an album, I think I’d love to get Norah Jones back in the studio and really let her produce that song the way that she wants to.

Haggard fans will thank you for getting this done, because it was like a big hole in American culture that he’s not had this kind of treatment.

I think so too, and I think it might help people to remember who he was. I mean, Dylan said, “He’s too big for Mount Rushmore.” And I think that in a lot of ways Merle is one of the only people that his connection to his craft stayed true. I love late Merle Haggard songs. His songwriting is so good. “Wishing All These Old Things Were New,” “I’ve Seen It Go Away” — all these amazing songs, and so, that talent never left. You know, a lot of our great people kind of peak and they fade out. His writing is so good throughout, and I think he used Dylan as inspiration because he said, “Everybody in the world knows Bob Dylan’s busting his ass to write another great song. Why aren’t I?”

Let’s go back to “Blue Moon,” then. At your tribute on the opening night of Telluride, you said something to the effect that you automatically turned down roles like Lorenz Hart nearly your entire life, because you wanted to stick to things that felt like they didn’t get too far away from your normal speaking voice or appearance, and say away from anything that was extremely physically transformative or involved really extreme voice alterations and that sort of thing. In a nutshell, it sounded like you’d been wary of getting too far outside your wheelhouse and doing something that didn’t feel like you. Well, with “Blue Moon,” and shaving your head bald and doing a big combover, and the east coast voice, you are so far from being recognizable. What was sticking closer to home in roles about?

Yeah, that’s what I really cared about when I was younger. And then that just slowly changed over time and I realized … it’s like expanding your definition of self. Like, if you’re really trying to work within the realms of naturalism, which is what acting been for the last 50 years, how do you expand what naturalistic means? And that just slowly started to cook for me in my brain, about developing different kinds of characters and stepping outside my comfort zone in expanding it. I mean really, John Brown [the abolitionist he played in the 2020 miniseries “The Good Lord Bird”] was the first really extreme version of that that I’d kind of gone with, and “Blue Moon” is a continuation of that.

What was fun is like, in the process of memorizing, I would just record things and send them to Rick, trying to find the right key of the movie. What does it sound like? What are the tells when you’re outside the period? You’re trying to hypnotize the audience, and anytime you violate the period, you break the hypnosis, you break the spell. And so finding the way he talked, making sure it wasn’t cute, making sure it was funny… This is a person who’s killing themselves with self-pity. I remember Peter Weir saying this to me once: “You know, self pity plays for exactly a fraction of a second.” [Snaps fingers.] “No, that’s too long.” A fraction of a second is enough. It’s a very hard emotion to dramatize. So there was so much to it.

sabrina lantos

It’s a tragedy at heart, more or less, but it helps that there are about 200 pretty funny lines in it, by my very rough estimation.

I giggled through the process of memorizing the script. It was so much fun to do, because I thought it was so funny. But it’s like Larry Hart lyrics. His lyrics are incredibly funny and absolutely heartbreaking. What’s the famous one… Oh shit. It’s the most famous song in the world. I played it on the trumpet as Chet Baker…

“My Funny Valentine.”

“My Funny Valentine.” The lyrics of that song are hysterical, but it’s absolutely heartbreaking at the same time.

It’s a phenomenal screenplay. Like, you wouldn’t even have to call him Lorenz Hart. It’s just a really interesting portrait of a man. The idea of setting it on the opening night of “Oklahoma!” in the middle of World War II, it’s a kind of moment where America’s shift had started, and Lorenz Hart is one of the people being left behind.

There are a lot of digs at Rodgers and Hammerstein in this movie, but you don’t have to make a choice between that and Rodgers & Hart.

I know. Richard Rodgers is a flat-out fucking genius, and he shows off his genius by being able to work with these two totally different lyricists. I mean, some people buckle at Hammerstein sentimentality and stuff like that, and Lorenz is so funny, but there’s no reason to knock either one of them.

There is desperation, if not self-pity, when he is throwing himself at Richard Rodgers or at Margaret Qualley’s character. As Hart, you are playing what maybe we used to call a “nebbish,” which is not something we really see in your filmography.

I think there are advantages (in this career) if you stay disciplined and focused… The great advantage of working with friends is that I don’t think anybody else in the world would have cast me in this part. It’s the fact that Rick knows me so well. If I insert another great director here, I doubt they would’ve cast me. And I’m really glad he did. But I think that’s what happens when you get to know people well over time: you know the hidden recesses of them that have that need to be mined.