Gus Van Sant is in top form with Dead Man’s Wire, a riveting true-crime dramatization of a hostage incident from 1977, during which Indianapolis man Tony Kiritzis, claiming that his mortgage broker had deliberately sabotaged his real estate investment, kidnapped the company president and rigged a sawn-off 12-gauge shotgun with a hair-trigger wire connected to his own neck. Scripted with fat-free economy by Austin Kolodney and made in the gritty, realistic style of Sidney Lumet’s ‘70s thrillers, the film pays tribute to Dog Day Afternoon while carving its own identity, led by a crackling performance full of unforced humor from Bill Skarsgard.

In addition to the primary reference of Lumet, there are reminders of other directors whose work captured the national disillusionment of the time, like Alan J. Pakula and Sydney Pollack, but also a link back to earlier Van Sant films. The casting in small roles of Kelly Lynch and John Robinson, respectively, recalls the raw, grainy look of Drugstore Cowboy, which is set in a similar timeframe (as were Milk and Van Sant’s last feature, the under-appreciated Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot); and the uninflected minimalism of Elephant.

Dead Man’s Wire

The Bottom Line

Power to the people.

Venue: Venice Film Festival (Out of Competition)

Cast: Bill Skarsgard, Dacre Montgomery, Al Pacino, Colman Domingo, Myha’la, Cary Elwes, Kelly Lynch, John Robinson, Todd Gable, Marc Helms, Michael Ashcroft, Neil Mulac, Daniel R. Hill

Director: Gus Van Sant

Screenwriter: Austin Kolodney

1 hour 44 minutes

The director’s affinity for outsiders makes no secret of where his sympathies lie, yet while other filmmakers might have turned Tony into a bona fide folk hero, Van Sant sticks to understatement, letting sociopolitical themes emerge organically.

High among other pluses this appealingly scrappy small-scale picture has going for it is a magnetically cool character part for Colman Domingo, oozing natural swagger and charisma as Fred Temple, a local radio deejay who learns that Skarsgard’s Tony is among his most ardent fans. The skill with which Fred is drawn into the standoff between Tony and law enforcement allows for some sly commentary on the very American obsession with celebrity access, in this case “the voice of Indianapolis.”

The other bonus is Fred’s fabulous playlist heard throughout (Roberta Flack, Barry White, Donna Summer and more), interwoven with Danny Elfman’s period-flavored score and used by Van Sant with strategic purpose. That runs from bangers like Deodato’s jazz-funk “Also Sprach Zarathustra” or Yes’ “I’ve Seen All Good People” through the folky freedom of Labo Siffre’s “Cannock Chase” (a seemingly counterintuitive choice as a pack of squad cars speed after Tony), to the sunshiny spiritual renewal of Harpers Bizarre’s “Witchi Tai To” cover.

The needle drops convey a subtle suggestion that whether Tony’s demands are met or not, he has made a statement that resonates with people by standing up to entitled fat cats like Al Pacino’s M.L. Hall, founder of the Meridian Mortgage Company, tucked away in Florida working on his leathery tan. Hence the use of B.J. Thomas’ “Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head,” which instantly evokes the outlaw resistance of the title characters in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

Van Sant’s intentions are more ambiguous with the electrifying explosion of Gil Scott-Heron’s power anthem “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” over the end credits. But it seems fair to interpret the spoken-word classic as an acknowledgement that while the push for social change had momentum back then, the country — and much of the world — has since swung in the opposite direction, toward rapacious capitalist greed at any cost. The stunning absence of empathy for “the little guy” in Pacino’s repugnant character feels uncomfortably familiar today.

Given that the three-day hostage crisis has little of the notoriety of other American true crimes, the less you know in advance about how it evolves — and how it’s resolved — the better. The basic facts are that Tony bought a piece of land with a commitment from a grocery company intending to lease the property to build a supermarket; Kiritzis claimed that Meridian then actively deterred renters after realizing the value of the land and squeezed him dry in a ploy to buy it back. Anyone who ever despaired about their outstanding mortgage remaining virtually static despite months of repayments will relate.

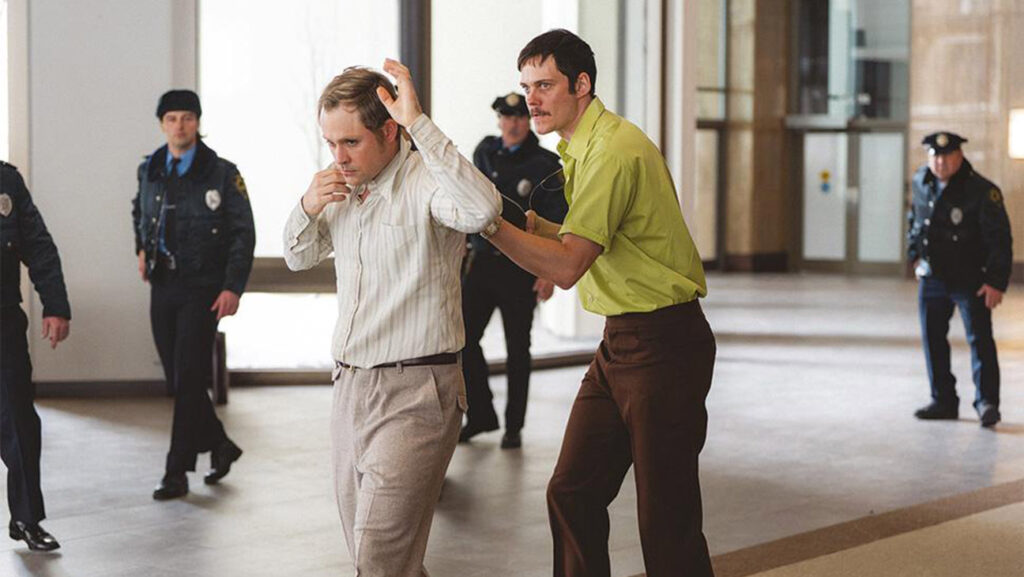

Showing up at the Meridian offices for an appointment with M.L. and learning that he’s on vacation, Tony instead enters the office of his son, Richard Hall (Dacre Montgomery). He rigs the carefully engineered wire contraption, ensuring that any attempt by his hostage to escape will result in Dick’s head getting blown off, also prohibiting police from shooting Tony for the same reason. Unlike most kidnappers looking to stay under the radar, Tony notifies the police from Dick’s office and seems unfazed by the crowd of armed officers and cop cars that gather as he transports the hostage across town to his apartment.

From the start, Skarsgard’s characterization makes him a disarming antihero, equal parts organized and chaotic. He gets amusing mileage out of Tony constantly apologizing for his coarse language and a big laugh when a priest blocks him on the street offering to wash away his sins: “Why don’t you wash my ass, father?” The kick he gets out of talking on the phone to Temple to clarify his demands and correct media misrepresentations is hilarious, introducing himself as “longtime listener, first-time caller.”

What he wants is complete debt forgiveness, $5 million in compensation and an apology from M.L., who is not at all inclined to oblige and seemingly unmoved by the threat to his son’s life. Australian actor Montgomery (Billy Hargrove on Stranger Things) looks unsurprised by his stubborn father’s reaction. He deftly balances calm with controlled panic, playing off Skarsgard’s nervy energy. One of the funniest visuals is Dick at the kitchen table in Tony’s apartment with the shotgun barrel facing him, his chin propped up on a book titled Urban Poor, Rural Forgotten.

Van Sant is in his element conducting the media circus and the brainstorming of local cops and FBI. The stakes are high but the tone is mostly buoyant and light, skewering the balance of power, wealth and privilege in America while playing it straight. In addition to callers voicing their support for Tony on Fred’s show, there’s also a whisper of solidarity from Linda Page (Industry discovery Myha’la), an enterprising young Black rookie TV news reporter in the right place at the right time, who refuses to be nudged to the sidelines by the “A-team” of white guys.

Kolodney’s script perhaps inevitably loses a little steam when Dick is finally released, though the developments that follow unfold with wry humor. Dead Man’s Wire is a timely, entertaining reflection on the way the offer of the American Dream often tends to be snatched back. But even if empty promises mean things don’t ultimately go the way Tony planned, his undiminished spirit is a victory in and of itself. And the fate of Meridian revealed in closing text doesn’t hurt either.