Solly’s Corner, a fast food restaurant in downtown Johannesburg, was bustling. Slabs of hake and golden chips sizzled, green chillies were being chopped and homemade sauces distributed liberally into packed sandwiches.

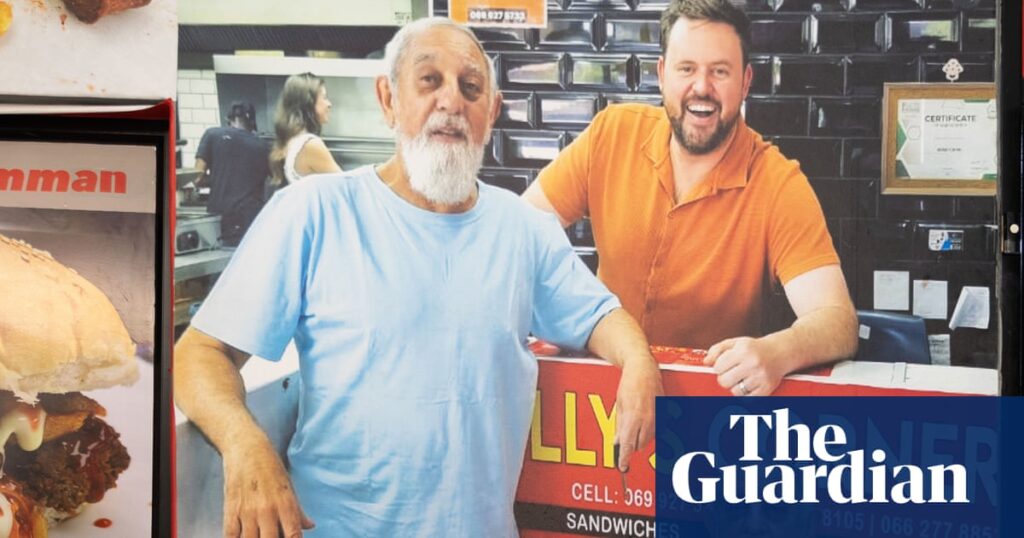

Food influencer and radio DJ Nick Hamman stepped behind the counter and was greeted as an old friend by Yoonas and Mohammed Akhalwaya, the father-son duo behind the family business in Fordsburg, a historical south Asian and Middle Eastern area.

Hamman, who has more than 200,000 followers on both Instagram and TikTok, has made it his mission for the past two years to boost food businesses across South Africa, highlighting the country’s diverse cuisine and bringing South Africans together across their often divided cultures.

Each video opens with a cheerful: “I’m Nick Hamman!” He then goes on to state his goal for the day, such as looking for the best burgers, boerewors sausages or breyani (biriyani). From mala mogodu intestine stew to magwinya doughnuts slathered with liver, there is seemingly nothing that Hamman won’t wholeheartedly enjoy.

“I started seeing food as a common theme in binding all of what I was interested in: culture, family, history, heritage,” said the 34-year-old, who also hosts the breakfast show on the radio station 5FM. “I believe food is political. I think food is very deeply tied to memory and nostalgia and history. And it tells the story of our country in a very special way.

“It’s a democracy in one way, so we get a lot of suggestions on social media … If you start to see a place being suggested 100 times or more, you get a good sense that you should probably go there.”

The entrepreneurs tick certain boxes: passionate about their food and culture, often with stories of overcoming adversity. Solly’s Corner also epitomises a type of business Hamman is fond of covering: a legendary spot that nevertheless remains something of a hidden gem.

Founded in 1956 by Yoonas’s mother, Khadija, the restaurant survived eviction in 1968 by the apartheid government’s Group Areas Act, which forced people to live in racially designated areas. It also made it through the Covid-19 pandemic and an electrical fire in 2021 that gutted the shop. “We’ve had our ups and downs, but we thank God above,” said Yoonas. “It’s an absolute blessing feeding people,” Mohammed added.

Hamman’s videos about Solly’s Corner have been viewed more than 1.7m times on TikTok, Instagram and Facebook since October 2023. The Akhalwayas were so appreciative of the extra 50-60% business that Hamman brought in, they plastered a huge image of him on a wall and named a burger after him. “Nick, also, he’s from the man upstairs,” Mohammed said warmly.

About 12 miles (19km) north, the township of Alexandra, often called just Alex, sits on steep slopes either side of a river. The towers of Sandton, known as “Africa’s richest square mile”, loom on the horizon. In a more affluent part of the township there is another type of entrepreneur that Hamman is drawn to: the young chef trying to uplift their area.

Gift Sedibeng founded Siga Culinary restaurant in 2018 in his parents’ old house, after a year working in a Mexican restaurant in Texas. The 33-year-old wanted to broaden his township’s tastebuds with fusion food, such as a towering “MexiKasi” kota burrito. An adaptation of the classic kota street food, a hollowed-out quarter white loaf is filled with everything from chips to chopped steak, a cheese burger and fried egg, plus Mexican twists including homemade pineapple salsa.

“I like it when you make a meal for a person and they express their love … It makes my heart melt,” Sedibeng said.

Sedibeng, who plans to open a culinary school next year, said about 60% of his customers come from outside Alex, then tell their friends that it is safe. “Crime is still there, but it’s not as bad as before,” he said.

Hamman hopes his videos can help to boost the local economy: “Places like Alex, for example, where there is brilliance … if we don’t present these spaces in ways that people are going to be enticed to come into them, the money’s never going to come into these areas and they aren’t going to be given a fair chance to develop.”

One of the worst-reputed places in Alex is Madala hostel, one of many built in townships by the apartheid government as men-only housing to control thousands of black male migrant workers. They became synonymous with the deadly political violence of the early 1990s, xenophobic killings in 2008 and continuing crime.

Hamman wanted to show that hostels are also host to a vibrant food culture. Where goats graze next to open sewers and rats scurry among rubbish, the rich smoke of barbecued meat can be found filling a walkway leading into Madala’s main courtyard.

A man who only gave his nickname, Mugabe, cooked shisanyama – a traditional Zulu braai: tender slices of beef steak, liver, heart and sausage, eaten with carrot and bean chakalaka salad, hot sauce and salt. On the hostel’s top floor, Mthunzi Ngema has been stewing inyama yenhloko, tender cow’s head meat, in dazzlingly clean silver vats since 1996.

While Mugabe and Ngema busied themselves with customers, Wandile “Wax” Dhlamini, an Alex local who acts as a guide to Madala, effused about the food. “In Zulu ceremonies we slaughter the cow and have the meat to feast, all the different parts,” he said. “More than anything, it’s a culture.”