Former and current bandmates, Columbia Records alumni, ex-managers, and a whole retinue of photographers, producers, engineers, and roadies who worked with Bruce Springsteen during the time he wrote and recorded his third album, “Born to Run,” all gathered in front of a capacity crowd at Monmouth University on Saturday to share their memories and stores about the album that made the Boss a superstar.

Sponsored by the Bruce Springsteen Archives & Center for American Music (which is housed at Monmouth), the event — which arrived at a high-profile moment around a different Springsteen album, with the Telluride Film Festival premiere of the “Nebraska”-era biopic “Deliver Me From Nowhere” and the announcement of the long-awaited deluxe edition of the album all taking place last week — was part of a multi-day series honoring the record’s role in Springsteen’s career and its place in American music history.

But this was still rock and roll, so there were special guests, audibles, arguments, agreements, reunions and surprises. One of the latter was the schedule slot labelled “LIVE PERFORMANCE: 5:15pm.” The schedule didn’t list speakers or panel participants, but there was a line of large draped items along the back of the stage of Monmouth University’s Pollak Theatre that looked suspiciously like amplifiers, drums and other musical equipment.

The mystery grew larger during introductory remarks pointing out the 11 a.m. lunch break, and noting that everyone needed to be back at the theater in a timely manner so they could once again lock up their phones in Yondr pouches before the afternoon’s events. This was a condition of the previous evening during a screening of rare film footage from the “Born to Run” recording sessions, assembled by Springsteen’s de facto video archivist, Thom Zimny. But no one in the audience was expecting that they’d be singing along to “Born to Run” and “Thunder Road” with Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band (along with special guests/former E Street bandmembers David Sancious and Ernest “Boom” Carter) by the end of the day.

An early conversation innocuously titled “At the Crossroads: Bruce Springsteen & Columbia Records” gave the audience a jolt of early energy. Facilitated by musicologist/DJ Rich Russo, the panel gathered three former Columbia employees (Peter Philbin, Paul Rappaport, and Michael Pillot) who had been staunch loyalists and supporters of Bruce Springsteen within Columbia when the rest of the label wasn’t so sure about this new guy who wasn’t selling as many records as they at first thought he would. They were joined by Mike Appel, Springsteen’s manager at the time.

The execs regaled the audience with endless stories about recalcitrant radio programmers, like a certain Los Angeles station’s music director who offered the feedback “I think he mumbles a lot,” upon first hearing “Born to Run”; Rappaport later sent that PD a telegram reading “Guess who just mumbled his way into the top ten in the first f*cking week.” Other radio stations may have found themselves the recipient of a Christmas stocking filled with actual coal courtesy manager Appel, who was dismayed at certain radio stations — like New York City’s own WNEW-FM — who refused to play Springsteen on the air. Appel also regaled the audience with his strategy that resulted in Springsteen getting on the cover of both Time and Newsweek. Apparently, he also turned down an interview request from Playboy because they wouldn’t give Bruce the cover. “I told them it would be more exciting.”

Also of note in the morning programs was the conversation between photographer Eric Meola — the man responsible for the images on the cover of Born to Run — and Springsteen’s younger sister Pam, also a professional photographer. Pam Springsteen was an engaging interviewer who brought technical knowledge and understanding to the conversation as well as an unsurprising warmth for the subject of Meola’s camera. (The archives are sponsoring an exhibit of Meola’s work from the cover session in a gallery on the Monmouth campus that’s open to the public until early December.)

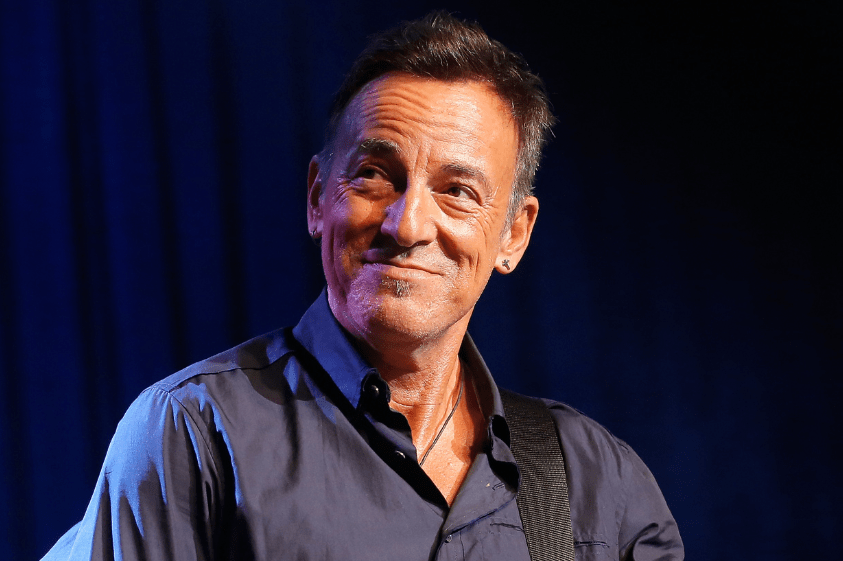

Returning from lunch break, the printed schedule was upended, pushing back a session entitled “Writing ‘Born to Run,’ the Song.” All was forgiven when two chairs were brought out and the center’s executive director, Robert Santelli, introduced his guest, the person who would know the most about the topic at hand: Mr. Bruce Springsteen. Over the course of the next 40 minutes, Springsteen — clad in his usual onstage gear of black pants and vest over a gray button-down shirt, looking sharp and newly-coiffed — would willingly talk about how he still writes in spiral notebooks, and how he heard that he’d sold 23,000 copies of his first record and wondered, “Who are all these people buying that record?”

Springsteen walked through the six months it took him to write the song, talking about listening to records at his “shotgun shack” at 7 ½ West End Court in Long Branch, and all of the individual ingredients he absorbed to inspire what he thought he wanted his next record to sound like: Duane Eddy, Phil Spector, the Beach Boys. “Guys, cars and girls, the basic subjects of rock and roll” — but he also knew he didn’t want to sound like a retro act. He also talked about how he taught himself to play piano by figuring out how to transpose guitar chords into piano chords while visiting maternal grandmother’s house, and that that Aeolian spinet piano ended up in his house in Long Branch, and it’s what he wrote the record on.

The next panel — “Writing ‘Born to Run,’ the Album” — brought Springsteen back out to sit with manager Jon Landau along with biographer Peter Ames Carlin. Springsteen shared that he’d recently taken a drive in the car with Jimmy Iovine — who was a young and aspiring engineer as he lied his way into the session once it had moved to the Record Plant — and they’d driven through Asbury Park and Springsteen’s actual hometown of Freehold, NJ, ending their trip at the house the record was written in. Springsteen recounted that when he finished “Born to Run” he brought the tape home to Long Branch and played it, and when it was done, he thought, “Yeah, that’s how I fucking sound…it’s still one of my favorite recordings.”

The relationship between artist and manager was best illuminated with this exchange, whether or not one agrees: “We were gonna make the greatest rock and roll record of all time,” Springsteen said. “That’s what we did,” answered Landau, quietly.

The symposium proceeded to take things to 11 with the next panel, promising a roundtable discussion on the making of the record. Landau and Springsteen returned to the stage along with ex-manager Appel, producer Jimmy Iovine, and the surviving members of the E Street Band from that time period: guitarist Steve Van Zandt, bassist Garry Tallent, pianist Roy Bittan and drummer Max Weinberg. For fans, it was fascinating to watch each person on the stage paying attention to the others as they talked — the facial expressions, the smiles, the nods of acknowledgement and understanding. Garry Tallent remained steadfast that he did not remember specifics of anything he was asked; Roy Bittan had nothing but good and positive words to say about every person he played with.

Steve Van Zandt got to retell the legendary story of the moment he joined the band. He had been hanging out in the studio, and the highly-paid professional session horn players that had been brought in for “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out” were not playing what anyone wanted them to play because no one in the studio knew how to tell them what they wanted, especially Springsteen. He asked Steve what he thought; Steve told his friend that he thought it sucked. His friend demanded that he go in and fix it. Van Zandt walked into the studio, told the horns to throw their charts away, and sang them their parts. “Those guys are screwing up my friend’s record,” is how he viewed the situation.

Conversely, this was Garry Tallent’s contribution to this panel:

“Garry, do you have any perspective from the bass player?”

Tallent turned on his microphone. “It took forever.” He turned it back off. When pressed, he turned the mic back on. “It had to be done, so I did it.”

“That’s the bass player,” Springsteen exclaimed.

Roy Bittan: “His playing was spectacular.”

Iovine was possibly the most visibly emotional during the roundtable, explaining how he’d never really mixed an album on his own before, but that he was sure he could do it. He did a dead-on imitation of what Springsteen sounded like standing behind him night after night: “No. Again. Again. Again.” Iovine explained that he had no idea who Springsteen was — “I never been in New Jersey!” he joked — and that he had never seen anything like the intensity offered by Springsteen and E Street in their recording sessions, but that he owed them everything because they taught him “how to be a person.”

But the final moment of the panel had clearly been planned, as there was an electric guitar adjacent to Van Zandt. Springsteen prefaced it by saying, “This is the greatest contribution Steve Van Zandt has ever made to my career.” On one of his visits to the studio, Van Zandt pointed out that he liked a certain minor chord on a riff in “Born to Run.” But he had an advantage in that he hadn’t heard the song several hundred times already, so he heard the chords more clearly and it was not what Springsteen had intended. “It would have been a total failure,” he insisted, had Van Zandt not pointed it out.

There’s a shop in Asbury Park that sells a now-infamous t-shirt that reads, “I HEARD BRUCE MIGHT SHOW UP.” Springsteen’s appearance at the symposium hadn’t been guaranteed, but his active, open participation on the panels was delightful and a little astonishing. And once he was there, it wasn’t out of the question that he’d pick up an acoustic guitar. But to get the entire E Street Band onstage — along with Boom Carter and David Sancious, who both played on “Born to Run” (their only released E Street Band recordings) — playing a full and loud rendition of both “Thunder Road” and “Born to Run” in a 700-seat theater was absolutely glorious.

The Springsteen Archives have staged previous symposia in honor of the first two Springsteen records (“Greetings from Asbury Park” and “The Wild, the Innocent, and the E Street Shuffle”) but those events were smaller by comparison to this year’s. According to Santelli, one of the goals of this year’s event was to “also demonstrate the kinds of programs the public can expect from the BSACAM once our brand-new home opens next year.” This year’s symposium has set a high bar to follow.