The Supreme Court of Nigeria should free Yahaya Sharif-Aminu and declare blasphemy laws in the country unconstitutional.

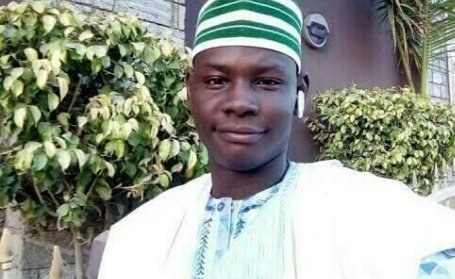

As a paradigm for the contemporary travails of free thought and freedom of worship, the ongoing saga of Yahaya Sharif-Aminu would be infuriating if it were not so depressing. The Nigerian musician, an adherent of the Tijaniyya Sufi Islamic order, has been running the legal gauntlet since he was first arrested in March 2020 for circulating via WhatsApp audio messages that apparently elevated Ibrahim Niasse, a Tijaniyya Muslim brotherhood Imam, above the prophet Muhammad.

Even before his August 2020 arraignment before a Kano State Upper-Sharia Court, which eventually found him guilty of “insulting the religious creed” contrary to the relevant section of the Kano State Sharia Penal Code Law (2000) and accordingly sentenced him to death by hanging, Sharif-Aminu was a dead man walking. Prior to his arrest by members of Hisbah, the state’s Islamic morality police, his family home had been razed to the ground by an incensed mob. From this standpoint, Sharif-Aminu’s fate was already sealed and his eventual conviction after a closed trial that was riddled with “serious procedural flaws,” a mere formality.

It was on account of these irregularities, among them the fact that Sharif-Aminu lacked legal representation that, in January 2021, a higher court overturned his conviction and ordered a retrial. In August 2022, the Kano State Appeals Court affirmed the retrial order, following which, in November 2022, Sharif-Aminu, unhappy at the appellate court’s decision to allow a retrial, decided to take his case to the Supreme Court of Nigeria, praying the apex court “not only to free him, but also to declare Kano State’s death penalty blasphemy law unconstitutional.”

Keep up with the latest headlines on WhatsApp | LinkedIn

Ordinarily, then, last week’s ruling by the same court granting Sharif- Aminu’s lawyers “permission to file an appeal outside the legally prescribed timeframe” bodes well for him, until you consider the following statement by Lamido Abba Sorondinki, counsel for the Kano State government, in defense of the original verdict: “This applicant made blasphemous statements against the Holy Prophet, which the government of Kano State will not condone. If the Supreme Court upholds the lower court’s decision, we will execute him publicly.” As if to avoid being misunderstood, he would go on to add: “Anybody that has uttered any word that touches the integrity of the holy prophet, we’ll punish him.”

We are afforded no other interpretation here. Mr. Sorondinki is daring his country’s ultimate legal arbiters: find in favor of Mr. Sharif-Aminu or watch us execute him. In other words, anything other than granting Sharif-Aminu’s prayer to free him–an outcome that is not guaranteed–and he is as good as dead.

Mr. Sorondinki’s statement, embarrassing and careless enough for a lawyer, never mind the appointed counsel for a whole state, is a reminder of everything that is wrong with the blasphemy charge originally preferred against Mr. Sharif-Aminu: the utter ridiculousness of it, and the reason why blasphemy laws have, for all intents and purposes, become a legal relic in most modern countries. Suppose, for the sake of argument, that the songs allegedly circulated by Mr. Sharif-Aminu via WhatsApp did indeed elevate Ibrahim Niasse over the prophet Muhammad; should that be enough to warrant or justify Mr. Sharif-Aminu’s execution? In a world of almost inexorable virality, are we also going to ferret out every individual who listened to, overheard, or came in contact with those songs one way or another and have them all executed? How many people are we allowed to kill simply for being exposed to an idea, image, or in this case, sound, that we disapprove of?

The difficulty in adducing justifiable answers to these questions, particularly under modern conditions where individuals living in close proximity and continuous interaction are bound to have not only different taboos, but conflicting conceptions and hierarchies of the sacred, is one of the many reasons why, over time, many Western societies have decided that prosecuting people for blasphemy is a fool’s errand. (Just to be clear, the modern idea is not that nothing is sacred; the modern idea is that you are not allowed to sacrifice the lives of others to propitiate your own idols.) The historical advance of reason has done the rest.

To say that progress in this regard has been uneven is an understatement. Nigeria is currently one of seven countries worldwide (the others are Afghanistan, Iran, Mauritania, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and Somalia) where blasphemy is punishable by death. According to Humanists International, at least eighty-nine countries continue to have blasphemy laws in their statutes. The United States International Commission on Religious Freedom pegs the number at seventy-one.

The variation in estimate does nothing to mitigate the seriousness of the problem, for as the situation in Muslim-majority northern Nigeria amply illustrates, blasphemy laws would be impossible without the prior popularity and acceptance of what Danish legal scholar Jacob Mchangama calls “the Fanatic’s Veto.” This is the idea that perceived blasphemy against the person of the prophet Muhammad warrants a sentence of death executable by the same individual or group of individuals who leveled the accusation. In this way, blasphemy violence sprouts from and authorizes a condition of permanent fatwa in which ordinary citizens are permitted to instigate violence against their fellow citizens in retaliation for real and perceived slights. Under such circumstances, it is impossible to think and speak freely.

This conservative temper contextualizes the Kano State counsel’s open threat to go after anyone who “touches the integrity of the holy prophet.” Mr. Sorondinki’s unfortunate words echo those of another Kano State dignitary, former State Governor Abdullahi Ganduje who, back in August 2020, promised to “waste no time in signing the warrant for the execution of the man who blasphemed.” At the time, both the Kano State chapter of the Nigerian Bar Association and the Muslim Lawyers Association of Nigeria expressed support for Mr. Ganduje’s position. Several Islamic clerics urged him to “do the right thing and not be distracted by activities of human right organizations.”

Not only does this explain the spike in blasphemy violence across northern Nigeria, it clarifies why no one is ever prosecuted for such violence and, most crucially, why, according to Amnesty International, “government officials rarely publicly condemn mob violence for blasphemy.” Official silence operates more or less as a license to kill.

Various international human and religious rights organizations have repeatedly called for Mr. Sharif-Aminu’s release. Unusual for the institution, the European Parliament has twice adopted an urgency resolution exhorting the Nigerian authorities to “immediately and unconditionally” release him. The leading defense counsel in the case, human rights lawyer Kola Alapinni, has argued that Sharia-based blasphemy laws across northern Nigeria violate the country’s secular constitution. Yet, if anything is clear from the statements of the authorities in Kano State, it is that they are merely going through the legal motions and would have Mr. Sharif-Aminu executed yesterday if they could.

The United States should put pressure on the Nigerian authorities to do the right thing and set Mr. Sharif-Aminu free. The offense for which he is being tried and has unjustly spent five years in detention has no place in a free society. It is the hallmark of inhumanity, and one that every decent nation has rightly disavowed.