British military equipment has been found on battlefields in Sudan, used by the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a paramilitary group accused of genocide, according to documents seen by the UN security council.

UK-manufactured small-arms target systems and British-made engines for armoured personnel carriers have been recovered from combat sites in a conflict that has now caused the world’s biggest humanitarian catastrophe.

The findings have again prompted scrutiny over Britain’s export of arms to the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which has been repeatedly accused of supplying weapons to the paramilitary RSF in Sudan.

They also raise questions for the UK government and its potential role in fuelling the conflict.

Months after the UN security council first received material alleging that the UAE may have supplied British-made items to the RSF, new data indicates that the British government went on to approve further exports to the Gulf state for military equipment of the same type.

British engines made specifically for a type of UAE-manufactured armoured personnel carrier also appear to have been exported to the Emirates, despite evidence that the vehicles had been used in Libya and Yemen in defiance of UN arms embargos.

The UAE has repeatedly denied allegations it gives military support to the RSF.

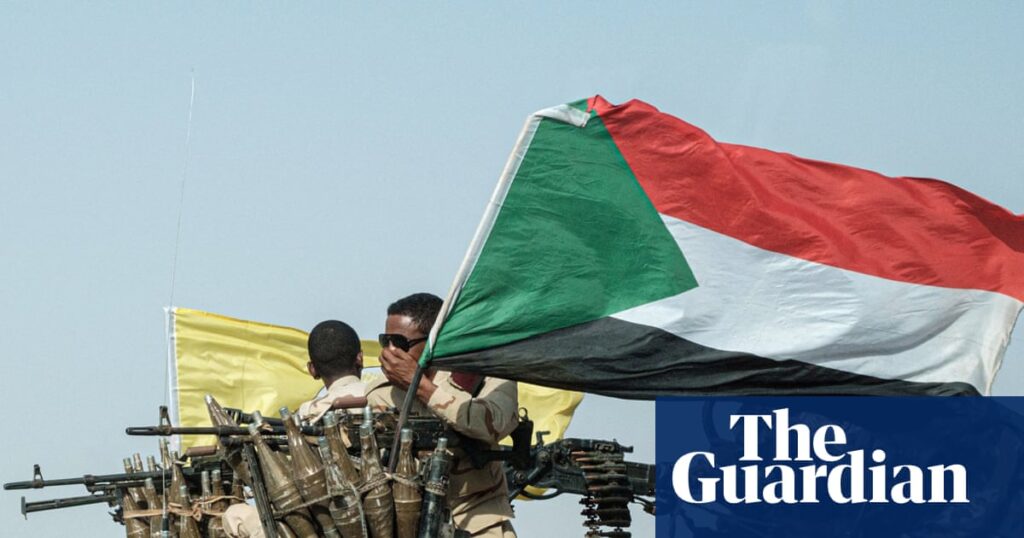

Now in its third year, the war between the RSF and Sudan’s military has killed at least 150,000 people, forced more than 12 million to flee their homes and left nearly 25 million facing acute hunger. Both sides are accused of war crimes and the targeting of civilians.

The UK military equipment found in Sudan features in two dossiers of material, dated June 2024 and March 2025, and seen by the security council. Both were compiled by the Sudanese military and claim to present detailed “evidence of UAE support” for the RSF.

Evidence that the UK continued supplying military equipment to the UAE, despite the risk it could end up fuelling Sudan’s ruinous conflict, has prompted deep concern.

Mike Lewis, a researcher and former member of the UN panel of experts on Sudan, said: “UK and treaty law straightforwardly obliges the government not to authorise arms exports where there is a clear risk of diversion – or use in international crimes.

“Security council investigators have documented in detail the UAE’s decade-long history of diverting arms to embargoed countries and to forces violating international humanitarian law.”

Lewis added: “Even before this further information about British-made equipment in Sudan, these licences should not have been issued, any more than to other governments responsible for arming the Sudan conflict.”

Abdallah Idriss Abugarda, chair of the UK-based Darfur Diaspora Association, which represens Sudanese from the western region of Darfur, called for an investigation into the issue.

“The international community, including the UK, must urgently investigate how this transfer occurred and ensure that no British technology or weaponry contributes to the suffering of innocent Sudanese civilians. Accountability and strict end use monitoring are essential to prevent further complicity in these grave crimes,” he said.

Images contained in the two dossiers of material seen by the security council – of which the UK is a permanent member – suggest that British-made small-arms target devices were recovered from former RSF sites in Sudan’s capital, Khartoum, and its twin city of Omdurman.

Although difficult to verify without metadata or precise geolocation information, several photographs are marked with labels indicating they were made by Militec, a manufacturer of small-arms training and target systems based in Mid Glamorgan, Wales.

Databases indicate that the UK government granted a number of licences to Militec to export items to the UAE as far back as 2013.

New information also reveals that between January 2015 and September 2024, the UK government issued 26 licences for the permanent export to the UAE of military training devices in the “ML14” category, which covers Militec’s products.

These licences were issued to 14 companies, including Militec. The government has refused to disclose which licences were granted to which companies.

The licences indicate that on 27 September 2024 – three months after the UN security council received images alleging the presence of ML14 rated small-arms equipment in Sudan – the UK government issued an “open individual export licence” for the same category of products to the UAE.

Such open licences allow Britain to export unlimited quantities of the equipment over the agreement’s lifespan, but without the need to monitor where it ultimately ends up.

By September 2024 there was growing concern that the UAE was arming Sudan’s RSF.

Nine months earlier in January 2024, a report by the UN panel of experts on Sudan – appointed by the security council to monitor Darfur’s arms embargo – stated that claims the Emirates were supplying weapons to the RSF were “credible”.

Years earlier, the UK government had also received evidence that UAE-based firms could be a diversion risk for small arms accessories. Three years earlier, the UK authorised exports of UK-made night-vision sights to a UAE business, which were subsequently procured by Taliban fighters in Afghanistan.

Militec was contacted, but declined to comment. It is understood that all of its exports are licensed by the relevant UK authorities and there is no wrongdoing by the company.

Images in the dossiers seen by UN diplomats show Nimr Ajban-series armoured personnel carriers (APCs) allegedly captured or recovered from RSF positions.

The Nimr Ajban APCs are manufactured in the UAE by the Edge Group, a primarily state-owned arms conglomerate.

A photograph in the 2025 document shows the data plate from the engine of a Nimr APC marked “Made in Great Britain by Cummins Inc” and indicates it was manufactured on 16 June 2016 by a UK subsidiary of Cummins, a US firm.

By 2016 the UK government was aware that the UAE had supplied Nimr APCs in violation of a UN arms embargo to armed groups in Libya and Somalia.

Evidence published by the security council stated that the UAE had supplied armoured vehicles to Zintani militias in Libya in 2013.

There appears to be no UK licence data to indicate when the British-made engine for the Nimr vehicles was exported because they are not solely designed for military equipment and do not require a special licence.

A Cummins spokesperson said: “Cummins has a strong compliance culture as evidenced by our 10 ethical principles set out in our code of business conduct. Our code explicitly covers compliance with applicable sanctions and export controls in the jurisdictions in which Cummins conducts business, and in some cases our policies go even further than applicable legal requirements.

“Cummins also has a strong policy against participating in any transaction – direct or indirect – with any arms embargoed destination without full and complete authorisation from the relevant governmental authorities.

“Cummins has a process to thoroughly review all defence transactions to evaluate legal and policy considerations, and under that program we have regularly obtained export licenses where legally required, as well as applied other compliance measures.

“With respect to Sudan specifically, we reviewed all our past transactions and did not identify any military transactions where Sudan was indicated as the end-use destination.”

A spokesperson for Britain’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office said: “The UK has one of the most robust and transparent export control regimes in the world. All export licences are assessed for the risk of diversion to an undesirable end user or end use.

“We expect all countries to comply with their obligations under existing UN sanctions regimes,” the FCDO said.

Sources said licensing decisions were made on a case-by-case basis and the UK was aware of the risk of diversion to the conflict in Sudan and that export licences, including those to the UAE, were regularly refused.